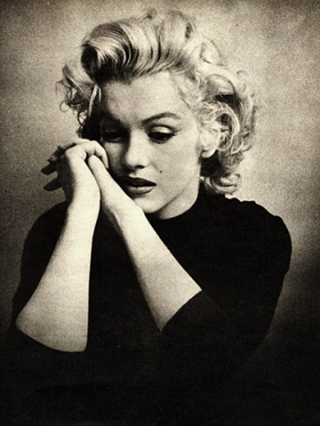

In the November issue, Vanity Fair published a previously unseen archive of Marilyn Monroe’s private writings. For all the millions of words she has inspired, Marilyn Monroe still remains something of a mystery. Now a sensational archive of the actress’s own writing—diaries, poems, and letters—is being published. With exclusive excerpts from the book, Fragments, the author enters the mind of a legend: the scars of sexual abuse; the pain of psychotherapy; the betrayal by her third husband, Arthur Miller; the constant spectre of hereditary madness; and the fierce determination to master her art.

Through the pages of Marilyn’s diaries, we see the whole arc of her tragic life: the transition from starlet to icon, her pursuit of true artistry beyond the “dumb blonde” she was pigeonholed as, and the troubled thoughts that followed her, from childhood, through three marriages, and, ultimately, to her final days. It is clear that the experience of writing was cathartic for her, providing a momentary grasp on the whirlwind of emotions that accompanied her life.

Marilyn left the archive, along with all her personal effects, to her acting teacher Lee Strasberg, but it would take a decade for her estate to be settled. Strasberg died in February 1982, outliving his most famous student by 20 years, and in October 1999 his third wife and widow, Anna Mizrahi Strasberg, auctioned off many of Marilyn’s possessions at Christie’s, netting over $13.4 million, but the Strasbergs continue to license her image, which brings in millions more a year. The main beneficiary is the Lee Strasberg Theatre & Film Institute, on 15th Street off Union Square, in New York City. It is, you might say, the house that Marilyn built.

Several years after inheriting the collection, Anna Strasberg found two boxes containing the current archive, and she arranged for the contents to be published this fall around the world—in the U.S. as Fragments: Poems, Intimate Notes, Letters by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. The archive is a sensational discovery for Marilyn’s biographers and for her fans, who still want to rescue her from the taint of suicide, from the accusations of tawdriness, from the layers of misconceptions and distortions written about her over the years.

--------------------------------------------------

At 17, she writes about the marriage and her jealousy of then husband James Dougherty, at times stepping back and analyzing her emotional state of mind. She wrote,

I was greatly attracted to him as one of the [“only” is crossed out] few young men I had no sexual repulsion for besides which it gave me a false sense of security to feel that he was endowed with more overwelming qualities which I did not possess—on paper it all begins to sound terribly logical but the secret midnight meetings the fugetive glance stolen in others company the sharing of the ocean, moon & stars and air aloneness made it a romantic adventure which a young, rather shy girl who didn’t always give that impression because of her desire to belong & develope can thrive on—I had always felt a need to live up to that expectation of my elders.

Her memory of that marriage revolves around her fear that Dougherty preferred a former girlfriend, which may have triggered Marilyn’s sense of unworthiness and vulnerability to men:

Finding myself ofhandedly stood up snubbed my first feeling was not of anger—but the numb pain of rejection & hurt at the destruction of some sort of edealistic image of true love.

My first impulse then was one of complete subjection humiliation, alonement to the male counterpart. (all this thought & writting has made my hands tremble …

She then wonders if this exercise in memory and self-analysis is in fact good for her, writing:

For someone like me its wrong to go through thorough self analisis—I do it enough in thought generalities enough.

Its not to much fun to know yourself to well or think you do—everyone needs a little conciet to carry them through & past the falls.

--------------------------------------------------

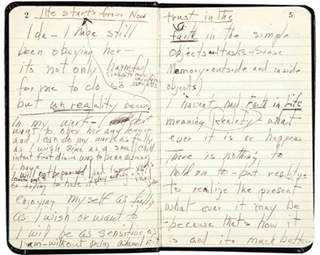

Described around 1955, this memory fully emerges, with the humiliating aftermath of being punished by her great-aunt Ida Martin, a strict, evangelical Christian paid by Grace Goddard to look after Norma Jeane for several months from 1937 to 1938. (Could this have been the sense-memory exercise that left her weeping in Strasberg’s acting class?) Marilyn wrote,

Ida—I have still

been obeying her—

it’s not only harmful

for me to do so

but unrealality because

life starts from Now

And later:

working (doing my tasks that I

have set for myself)

On the stage—I will

not be punished for it

or be whipped

or be threatened

or not be loved

or sent to hell to burn with bad people

feeling that I am also bad.

or be afraid of my [genitals] being

or ashamed

exposed known and seen—

so what

or ashamed of my

sensitive feelings—

--------------------------------------------------

In one of the handful of sweet and affecting poems included in this archive, Marilyn, still in the first flush of her love for Arthur Miller and imagining what he might have been like as a young boy, wrote a poem about him:

my love sleeps besides me—

in the faint light—I see his manly jaw

give way—and the mouth of his

boyhood returns

with a softness softer

its sensitiveness trembling

in stillness

his eyes must have look out

wonderously from the cave of the little

boy—when the things he did not understand—

he forgot

The poem then turns dark, a premonition, perhaps, of how the marriage would end:

but will he look like this when he is dead

oh unbearable fact inevitable

yet sooner would I rather his love die

than/or him?

--------------------------------------------------

While staying in England for the production of The Prince and the Showgirl, Marilyn stumbled upon a diary entry of Arthur Miller’s in which he complained that he was “disappointed” in her, and sometimes embarrassed by her in front of his friends.

Marilyn was devastated. One of her greatest fears—that of disappointing those she loved—had come true. His betrayal confirmed what she’d “always been deeply terrified” of: “To really be someone’s wife since I know from life one cannot love another, ever, really,” as she wrote in another “Record” journal entry.

fter this discovery, Marilyn found it so difficult to work that she flew in Dr. Hohenberg from New York. She was having trouble sleeping, relying on barbiturates. On Parkside House stationery, she wrote one night after Miller had gone to bed:

on the screen of pitch blackness

comes/reappears the shapes of monsters

my most steadfast companions …

and the world is sleeping

ah peace I need you—even a

peaceful monster.

--------------------------------------------------

In the summer of 1957, the couple bought a country house in Roxbury, Connecticut. That winter Miller worked on adapting one of his short stories for the screen, “The Misfits,” while Marilyn grappled with her feelings of disappointment and loss:

Starting tomorrow I will take care of myself for that’s all I really have and as I see it now have ever had. Roxbury—I’ve tried to imagine spring all winter—it’s here and I still feel hopeless. I think I hate it here because there is no love here anymore…

In every spring the green [of the ancient maples] is too sharp—though the delicacy in their form is sweet and uncertain—it puts up a good struggle in the wind—trembling all the while… I think I am very lonely—my mind jumps. I see myself in the mirror now, brow furrowed—if I lean close I’ll see—what I don’t want to know—tension, sadness, disappointment, my [“blue” is crossed out] eyes dulled, cheeks flushed with capillaries that look like rivers on maps—hair lying like snakes. The mouth makes me the sadd[est], next to my dead eyes…

When one wants to stay alone as my love (Arthur) indicates the other must stay apart.

--------------------------------------------------

In 1958, Marilyn moved back to Los Angeles to begin work in Some Like It Hot, which—despite her chronic lateness and other difficulties on the set—would turn out to be her greatest and most successful comedy. She began recording her musings and poems in a red spiral Livewire notebook, poems that took a dark turn. Here’s one such fragment, written under the ironic heading “After one year of analysis”:

Help help

Help

I feel life coming closer

when all I want

Is to die.

Scream—

You began and ended in air

but where was the middle?

--------------------------------------------------

In July of 1960, filming began in the Nevada desert for The Misfits, under John Huston’s direction, with Marilyn, Clark Gable, Montgomery Clift, Thelma Ritter, and Eli Wallach in key roles. On the set he met and fell in love with a photographic archivist on the film, Inge Morath, who would become his third wife. On November 11, 1960, Marilyn and Arthur Miller’s separation was announced to the press.

Three months later, back in New York, emotionally exhausted and under Dr. Kris’s care, Marilyn was committed to Payne Whitney’s psychiatric ward. What was supposed to have been a prescribed rest cure for the overwrought and insomniac actress turned out to be the most harrowing three days of her life.

Kris had driven Marilyn to the sprawling, white-brick New York Hospital—Weill Cornell Medical Center, overlooking the East River at 68th Street. Swathed in a fur coat and using the name Faye Miller, she signed the papers to admit herself, but she quickly found she was being escorted not to a place where she could rest but to a padded room in a locked psychiatric ward. The more she sobbed and begged to be let out, banging on the steel doors, the more the psychiatric staff believed she was indeed psychotic. She was threatened with a straitjacket, and her clothes and purse were taken from her. She was given a forced bath and put into a hospital gown.

On March 1 and 2, 1961, Marilyn wrote an extraordinary, six-page letter to Dr. Greenson vividly describing her ordeal: “There was no empathy at Payne-Whitney—it had a very bad effect—they asked me after putting me in a ‘cell’ (I mean cement blocks and all) for very disturbed depressed patients (except I felt I was in some kind of prison for a crime I hadn’t committed. The inhumanity there I found archaic … everything was under lock and key … the doors have windows so patients can be visible all the time, also, the violence and markings still remain on the walls from former patients.)”

A psychiatrist came in and gave her a physical exam, “including examining the breast for lumps.” She objected, telling him that she’d had a complete physical less than a month before, but that didn’t deter him. After being unable to make a phone call, she felt imprisoned, and so she turned to her actor’s training to find a way out: “I got the idea from a movie I made once called ‘Don’t Bother to Knock,’ ” she wrote to Greenson—an early film in which she had played a disturbed teenage babysitter.

I picked up a light-weight chair and slammed it … against the glass intentionally. It took a lot of banging to get even a small piece of glass—so I went over with the glass concealed in my hand and sat quietly on the bed waiting for them to come in. They did, and I said to them “if you are going to treat me like a nut I’ll act like a nut.”

She threatened to harm herself with the glass if they didn’t let her out, but cutting herself was “the furthest thing from my mind at that moment since you know Dr. Greenson I’m an actress and would never intentionally mark or mar myself, I’m just that vain. Remember when I tried to do away with myself I did it very carefully with ten seconal and ten tuonal and swallowed them with relief (that’s how I felt at the time.)”

When she refused to cooperate with the staff, “two hefty men and two hefty women” picked her up by all fours and carried her in the elevator to the seventh floor of the hospital. (“I must say that at least they had the decency to carry me face down.… I just wept quietly all the way there,” she wrote.)

She was ordered to take another bath—her second since arriving—and then the head administrator came in to question her. “He told me I was a very, very sick girl and had been a very, very sick girl for many years.”

Dr. Kris, who had promised to see her the day after her confinement, failed to show up, and neither Lee Strasberg nor his wife, Paula, to whom she finally managed to write, could get her released, as they were not family. It was Joe DiMaggio who rescued her, swooping in against the objections of the doctors and nurses and removing her from the ward. (He and Marilyn had had something of a reconciliation that Christmas, when DiMaggio sent her “a forest-full of poinsettias.”)

It should be noted that this is one of the few letters that have already seen the light of day.:

Someone when I mentioned his name you used to frown with your moustache and look up at the ceiling. Guess who? He has been (secretly) a very tender friend. I know you won’t believe this but you must trust me with my instincts. It was sort of a fling on the wing. I had never done that before but now I have—but he is very unselfish in bed.

From Yves [Montand] I have heard nothing—but I don’t mind since I have such a strong, tender, wonderful memory.

I am almost weeping.

--------------------------------------------------

In November 1961, Marilyn met John F. Kennedy at the Santa Monica home of actor Peter Lawford, the president’s brother-in-law. The following year, in February, she bought her first home, in fashionable Brentwood. She began filming her last movie, Something’s Got to Give, directed by George Cukor, in April of 1962. The now famous outtakes from the unfinished film—Marilyn rising naked and un-shy from a swimming pool—show her fit and radiant, at the top of her game. Her chronic lateness and absences from the set, however—something even Strasberg couldn’t cure her of—caused her to be fired from the picture, which was never completed. Four months later, on August 5, 1962, she would be found dead from a drug overdose in her Brentwood home, an apparent suicide.

Even with the revelations and unexpected pleasures of this soon-to-be-published archive, the deep mystery of her death remains. For those who believe that Marilyn’s death was indeed a suicide, there are many indications of her emotional fragility and a description of a past suicide attempt. “Oh Paula,” she wrote in an undated note to Paula Strasberg, “I wish I knew why I am so anguished. I think maybe I’m crazy like all the other members of my family were, when I was sick I was sure I was. I’m so glad you are with me here!”

For those who believe she died of an accidental overdose, mixing prescribed barbiturates with alcohol, the archive contains evidence of her optimism, her feeling that she has come to rely on herself and will solve her problems through work and her capable, businesslike plans for the future.

And for conspiracy theorists who have always suspected foul play, there is an intriguing note to the effect that Marilyn might have distrusted and even feared J.F.K.’s brother-in-law Peter Lawford, who was the last person to speak to her on the phone. In the handsome, green, engraved Italian diary, probably dating to around 1956, she had appended this fearful note to a short list of people she loved and trusted:

the feeling of violence I’ve had lately

about being afraid

of Peter he might

harm me,

poison me, etc.

why—strange look in his eyes—strange

behavior

in fact now I think I know

why he’s been here so long

because I have a need to

be frighten[ed]—and nothing really

in my personal relationships

(and dealings) lately

have been frightening me—except

for him—I felt very uneasy at different

times with him—the real reason

I was afraid of him—is because I believe

him to be homosexual—not in the

way I love & respect and admire [Jack]

who I feel feels I have talent

and wouldn’t be jealous

of me because I wouldn’t

really want to

be me

whereas Peter wants

to be a woman—and

would like to be me—I think

Marilyn and Lawford, the British actor and bon vivant, had first met in Hollywood in the 1950s. “Jack” is probably Jack Cole, the dancer-choreographer who befriended and coached Marilyn on Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and There’s No Business Like Show Business. (She would not meet “Jack” Kennedy until five years later.)

If this archive doesn’t quite solve the enigma of Marilyn Monroe’s death, it does go deeper than we have ever been into the mystery of her life. As Lee Strasberg noted in his eloquent eulogy, “In her eyes and mine, her career was just beginning. The dream of her talent, which she had nurtured as a child, was not a mirage.”

In other entries, Marilyn wrote:

“I haven’t had Faith in Life

meaning Reality—what

ever it is

or happens

There is nothing to

hold on to—but reality

to realize the present

whatever it may be

—because that’s how it

is and it’s much better”

“A full physical checkup with a medical doctor may be wise”: Marilyn actually suffered from severe endometriosis (a condition in which uterine issue grows outside the uterus) her entire life, which may have contributed to her miscarriages and to an ectopic pregnancy later in life.

“Fear of giving me the lines new

maybe I won’t be able to learn them

maybe I’ll make mistakes

people will think I’m no good or laugh or belittle me or think I can’t act.”

“I’m not very bright I guess.

No just dumb/if I had

Any brains I wouldn’t be

On crummy train with this

Crummy girl’s band”

“I would never intentionally mark or mar myself, I’m just that vain. Remember when I tried to do away with myself I did it very carefully with ten Seconol and ten Tuinol and swallowed them with relief (that’s how I felt at the time).”

No comments:

Post a Comment